by H. B. Auld, Jr.

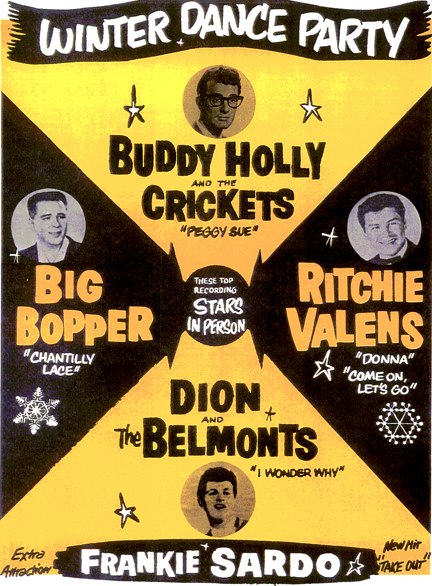

Sixty-five years ago today on February 3, 1959, was the day later referred to as “The Day The Music Died.” That was the day future rock and roll legends Buddy Holly, J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and Ritchie Valens all died in a plane crash in Iowa. They were just 22, 28, and 17 years old, respectively.

Buddy Holly and his band, The Crickets, from Lubbock, Texas, were just beginning their rise to musical stardom. They had opened in the Lubbock area for other artists, including a then relatively unknown named Elvis Presley. They began playing when Buddy was in high school, and this was a chance to tour the USA. The Winter Dance Party Tour had just finished a concert in Clear Lake, IA, and were headed to their next gig in Moorhead, MN, the next night. Other future stars on the same tour included Dion DiMucci and the Belmonts.

The whole group was traveling in a bus with frequent mechanical difficulties when a snow and ice storm made travel difficult. Buddy chartered a small private Beechcraft Bonanza aircraft to fly him and his band to Moorhead. Richardson, who had the flu, convinced Crickets bass player Waylon Jennings to give up his seat to J.P. Afterward, Buddy told Waylon, “I hope your ol’ bus freezes up.” And Waylon replied to Buddy, “Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes.” Waylon said he regretted those final words to Buddy for the rest of his life. And young Ritchie Valens beat out Crickets guitarist Tommy Allsup in a coin flip for the remaining seat on the plane. Ironically, Ritchie was then overheard saying, “That’s the only thing I ever won in my life.” The remaining Cricket drummer, Carl Bunch, would also take the bus. Flying the plane was a relatively inexperienced 21-year-old pilot named Roger Peterson. All were killed soon after take-off when the plane crashed into a farm field just six miles from the Mason City Airport, from which the aircraft departed five minutes earlier at 12:55 a.m. The plane had bounced and rolled over before flipping tail-over-nose several times. The pilot was found still strapped into the cockpit. All the passengers were ejected from the plane and lay near the crash site. All were killed instantly.

Buddy had already written many songs that became hits after his death. Songs like “Peggy Sue,” “Oh, Boy!” “Maybe Baby,” “True Love Ways,” “Rave On,” “It’s So Easy To Fall In Love,” “Everyday,” “Not Fade Away,” “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” “Heartbeat,” “Raining in My Heart,” “Words of Love,” and a recent number one hit “That’ll Be The Day,” became rock and roll classics covered by scores of other artists down through the years.

In another ironic twist, when word of the plane crash and the death of the tour stars reached the venue at Moorhead, MN, word went out to try to find another local act for the concert that night. A 15-year-old local boy named Robert Thomas Velline and his band of hastily assembled friends, including his brother Bill, went on that night calling themselves The Shadows. Robert Velline soon found rock and roll success and stardom as Bobby Vee with a string of hits of his own.

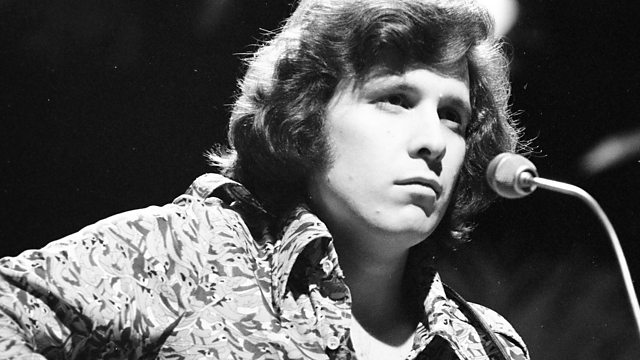

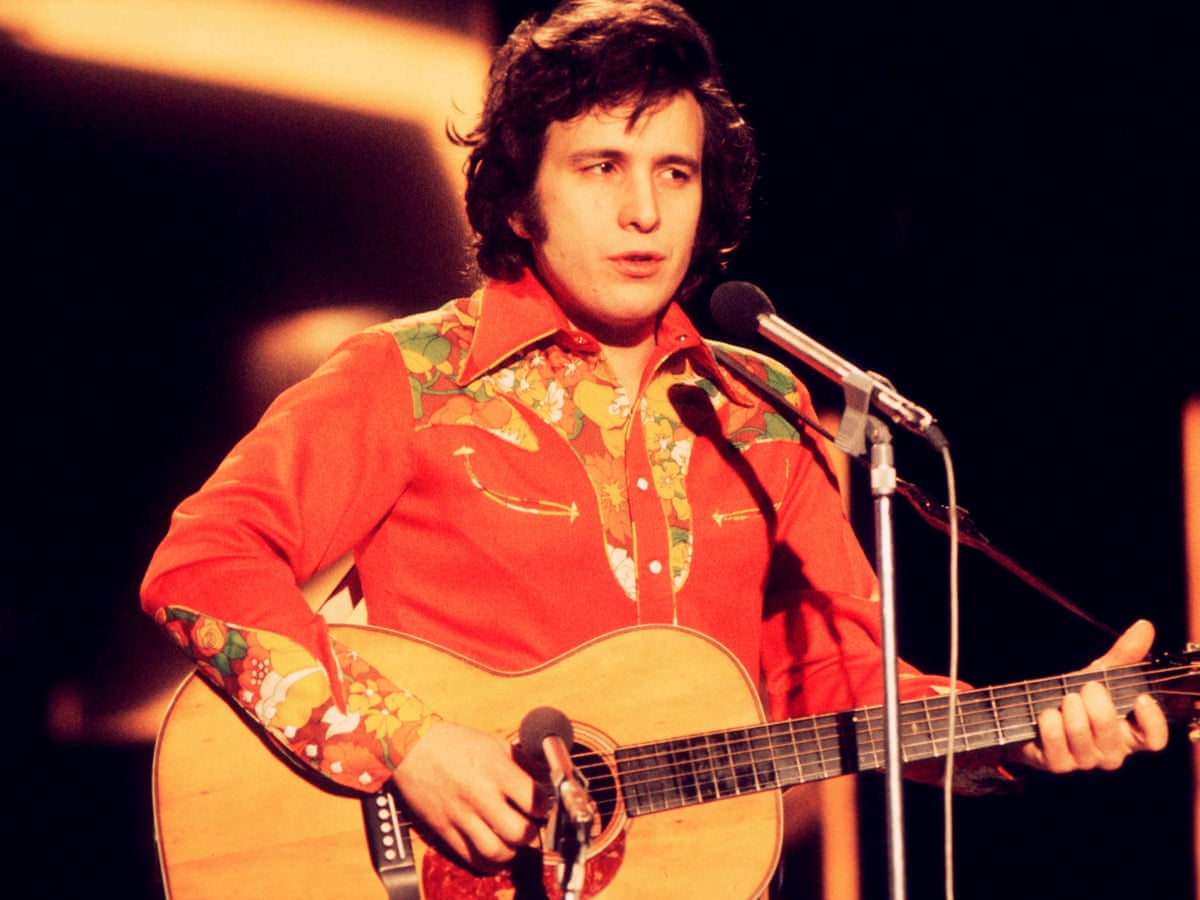

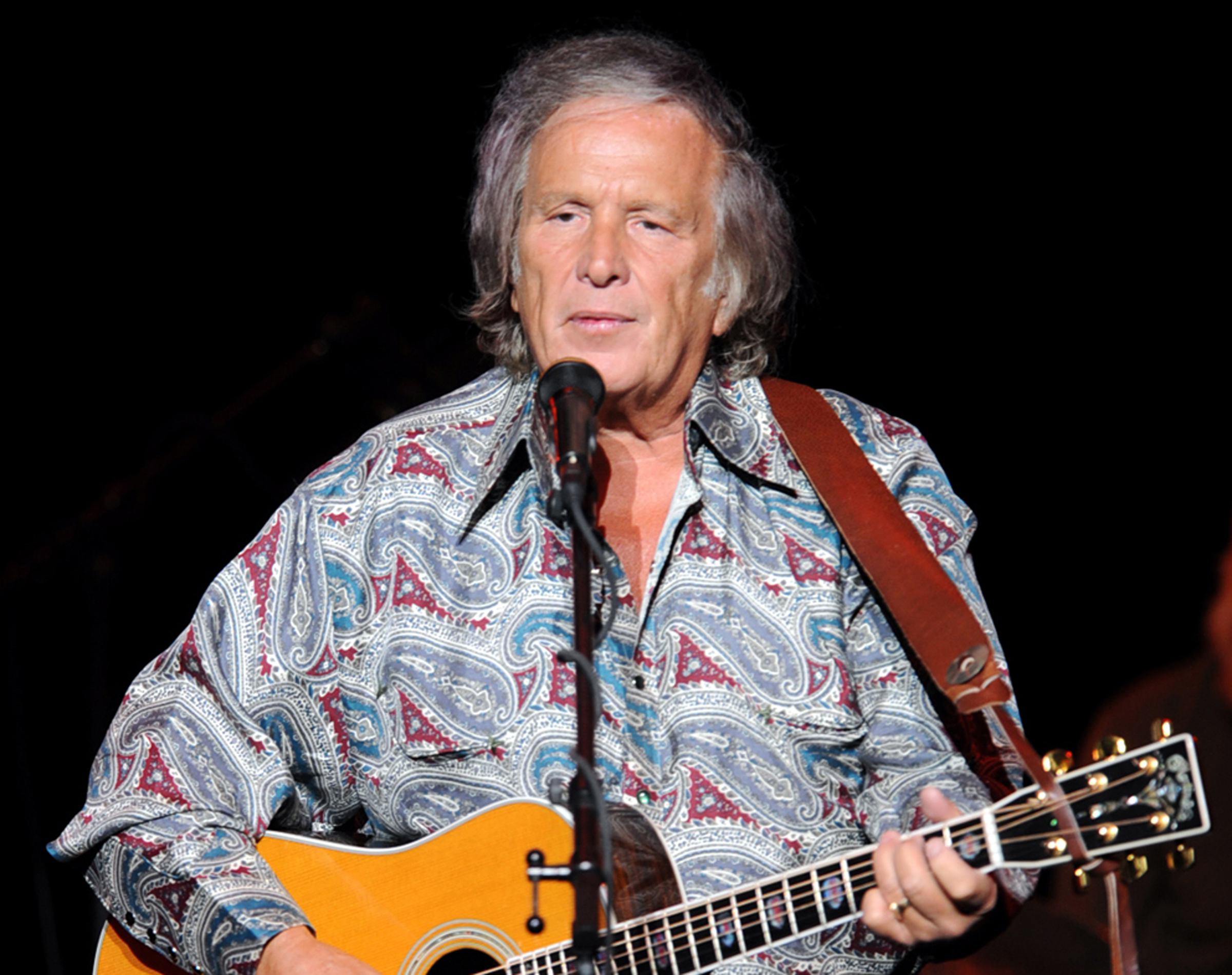

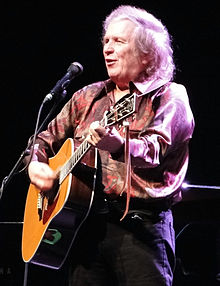

The early morning that the three rock stars crashed and died, February 3, 1959, became known as “The Day the Music Died,” as popularized in a 1971 hit song by Don McLean, entitled “American Pie.”